OUR STORY

The Saigon Siblings Story

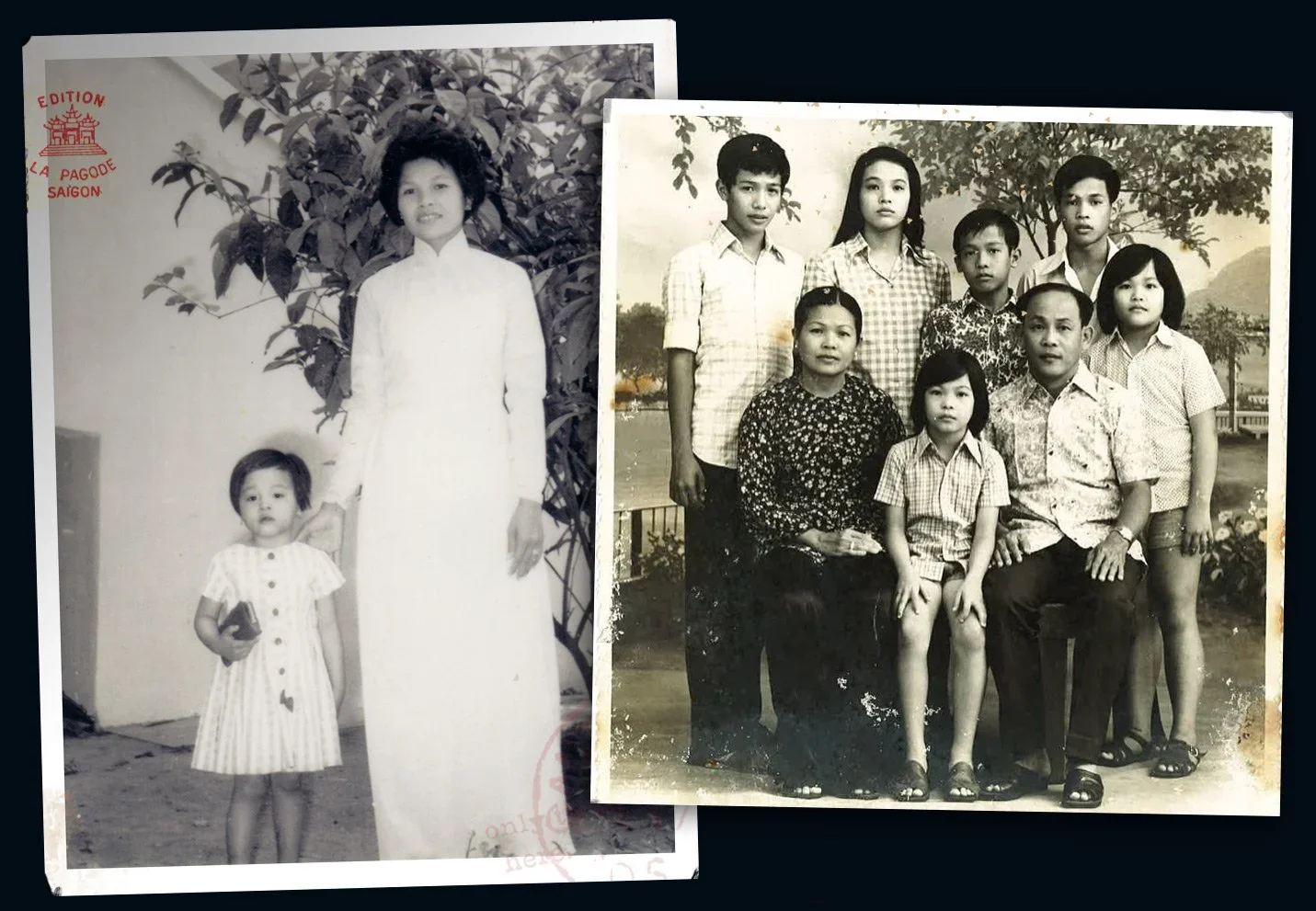

In 1975 Mr. Thanh Minh Banh and his wife Phung owned several enterprises, including a nail factory and an ice factory, with several locations along the Mekong Delta while living somewhat comfortably in Saigon. Life was good. Business was good. And they had six healthy children to show for it—three sisters and three brothers. But, as many of these stories go, things soon took a turn for the worse. As Saigon fell to the Communists in 1975, Mr. Banh was allowed to keep running his factories, but he could see that the future was not so bright. The government was indeed seeking to control the means of production, and it probably wouldn’t be too long before they would completely seize control of Mr. Banh’s business entirely. The very business that he had built by himself from the ground up. So, he started planning his family’s escape to the west. Mr. Banh really wanted an education for his kids, and a good life for he and his wife, and that prospect no longer seemed possible in this new version of Saigon.

Due West

In 1977 his oldest son Albert got out of the country first with help from an uncle, and he made his way to the very aptly named Alberta, Canada. From there, Mr. Banh starting planning a second escape with the rest of the clan. But on the eve of their exodus, he got caught in the middle of the night while loading a hired boat with all of their belongings, and was carried off to prison. Luckily, he had still had some money left, and he was able to pay his way out after three months behind bars. Undeterred, he tried again six months later. With his wife and five remaining children in tow once again, they boarded a boat in the middle of the night, made it to open water, and headed straight for the coast of Malaysia. They were finally in the wind.

They made their way to Bidong Island off the northeast coast and pointed the boat straight for the beach. During the mad scramble to get ashore, chaos ensued as everybody rushed in different directions clinging to the only belongings they had left in the world. As the Banh family made their way from the surf toward higher ground, they soon realized there were only six of them left. The youngest sibling, Yen, who was seven at the time, was no longer with the group. Frantically, they searched up and down the beach fearing the worst, when finally a fellow traveler approached with a scared girl in his arms asking if they were looking for someone. That rude awakening would set the stage for a yearlong trial in Malaysia’s rapidly growing Vietnamese refugee community.

Malay Camping

Inside the camp they were assigned a ramshackle wooden hut, and all seven Banhs lived crammed into a single room sleeping shoulder to shoulder. During the day, the kids found tasks for themselves by trailing behind the many aunties and uncles, looking for odd jobs, and trying to pass the time. Eric, the youngest brother of the three, got pretty good at fishing and would sell a few fish to neighbors, while saving a few for that night’s dinner. Sophie learned making moon cakes with some of the aunties nearby. As you might guess, this learned work ethic would pay off much further down the road.

They were all given a daily ration of canned sardines, and to this day, a couple of the Banh siblings are not fond of these salty fish after eating so many for so long. On Thursdays they would get to share a canned chicken, and that meal became something to look forward to. It became a weekly “Refugee Thanksgiving” of sorts, and the slow thunk of the chicken sliding out of the can and landing on the plate meant it was dinner time. Eric remembers longing for some grilled pork skewers from District 1 back in Saigon, but his Muslim hosts weren’t about to oblige the youngster any time soon.

After waiting for over a year for news of a visa, they were finally granted entry to Canada thanks to the family’s connections to Albert and other relatives now living there. They were soon moved to Kuala Lumpur on the mainland for processing, and awaited the next leg of their journey.

Northern Light

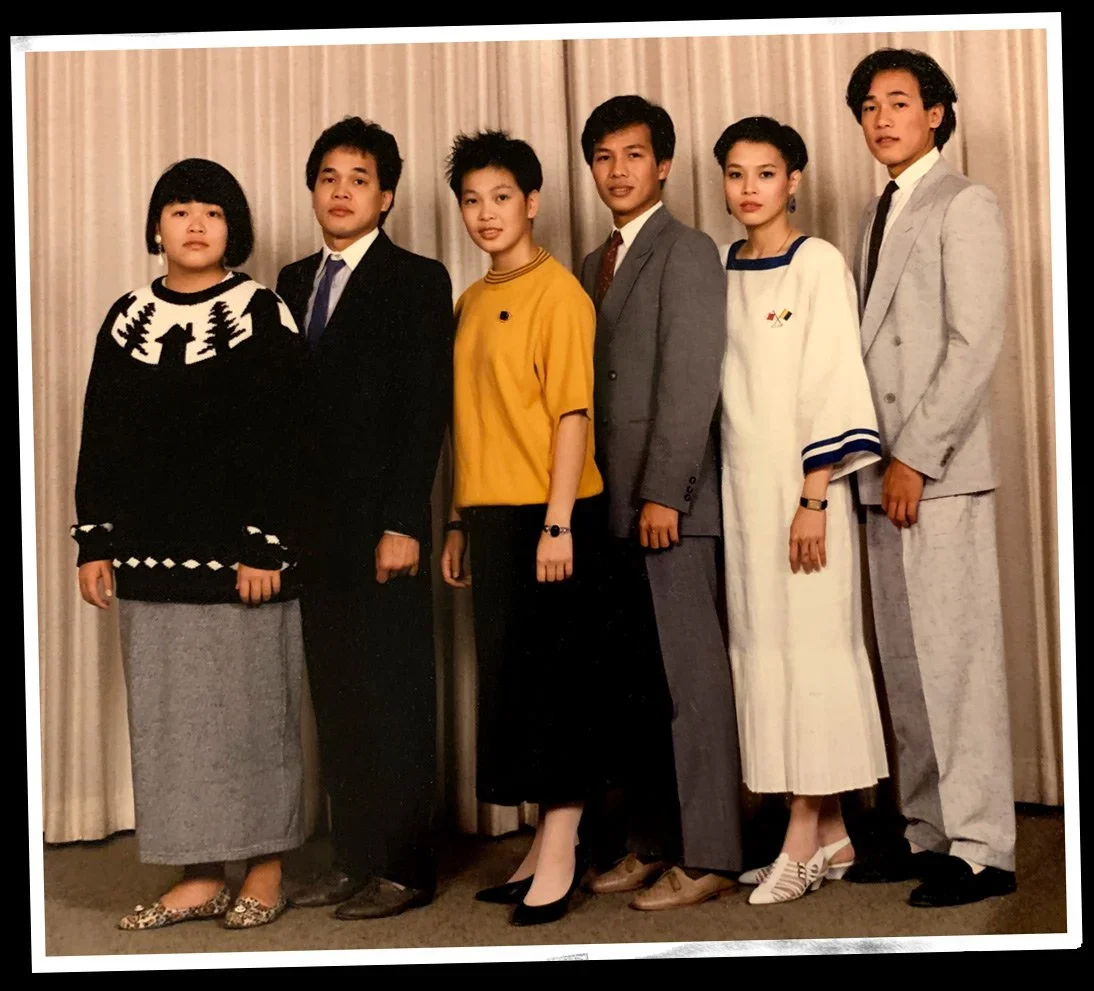

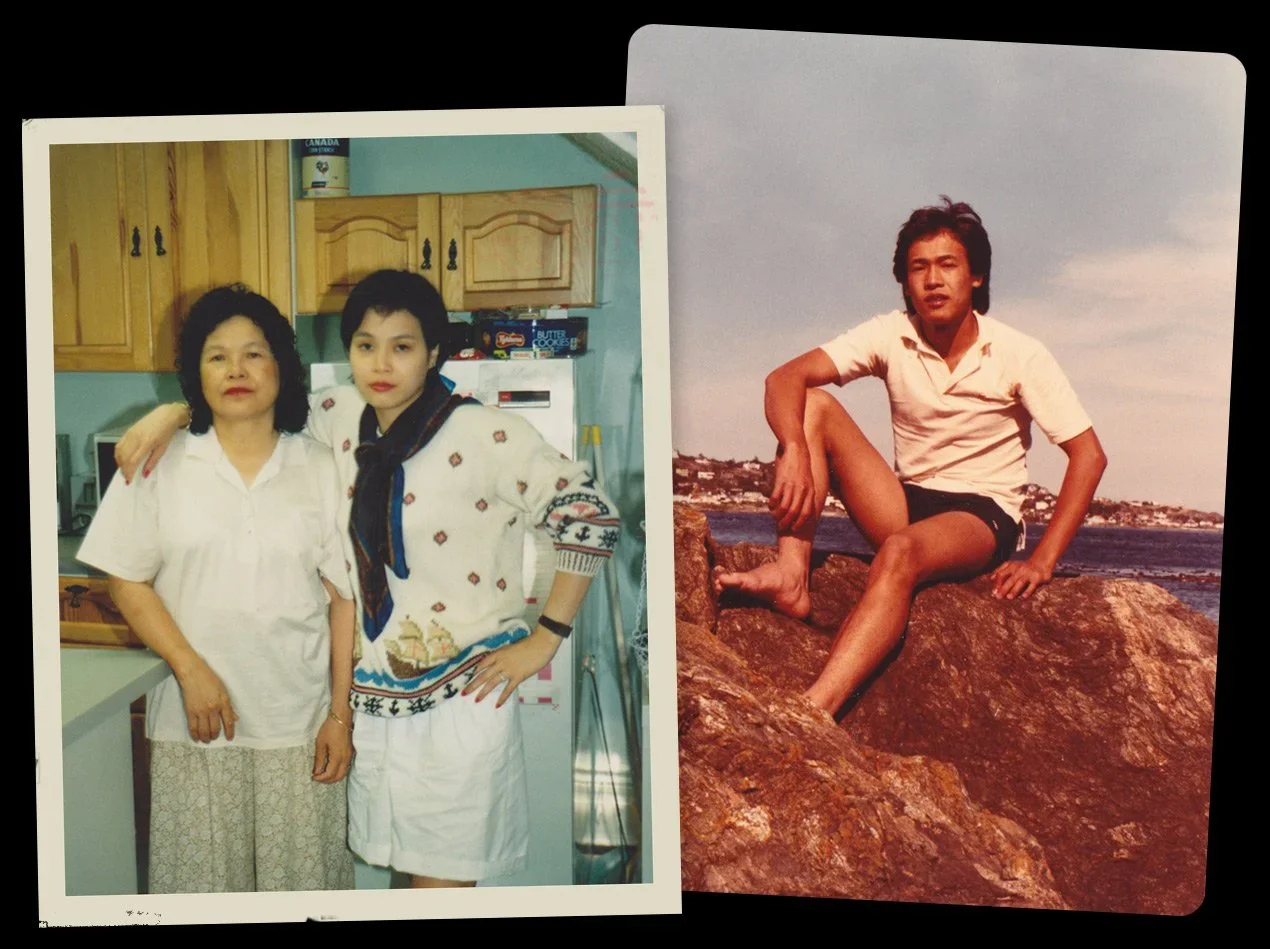

Arriving in Edmonton, Alberta toward the end of December in 1979 was quite a shock for these weary travelers, but they were happy to be reunited with brother Albert. All the newcomers soon became ill in the now sub zero temperatures, but they made due, and they didn’t let up for a second. Mom got to work sewing jeans at the Great Western Garment Company during the day, and then spent time washing dishes at a downtown hotel at night. Dad was working various factory jobs and even had a brief stint as a handyman at a church. The elder Banh eventually tried opening a restaurant, but it didn’t quite pan out. Mr. Banh’s main focus was to make enough money to get all of the kids through school, and then ultimately into college. He had an intense work ethic and he wanted everybody to get good jobs and become bankers, lawyers, doctors and the like. Eric’s older brother Albert didn’t enjoy school all that much, plus he had already been in Canada for a year now looking for work, so he was the first to break dad’s heart by getting a job in a restaurant. Albert loved cooking, but back in those days, restaurant work wasn’t much of a glamour profession like it is often depicted today (there was no Food Network to speak of) but he was determined, and a seed was planted in the collective minds of the Banhs. Albert worked his way up the ladder to sous chef and eventually got his brother Eric hired to wash dishes and peel potatoes.

After a few years, the Banh parents embraced the restaurant idea again and opened the first Vietnamese restaurant in Edmonton. They purchased a well known breakfast place called The Lighthouse in the Westside’s 107th Avenue neighborhood. While they kept the Lighthouse name and continued to prepare standard breakfast fare (eggs & bacon, waffles, omelettes), they would also introduce a handful of specials to the menu to see if the locals might be interested in sampling Vietnamese home cooking. It actually went well. Soon enough, phở was served regularly and quite a few Edmontonians could now pronounce bánh xèo. This was 1984.

Southern Exposure

A few years back Sophie had met her future (and current) husband Sowady Chhoukdean, who had come to Edmonton from Cambodia—fleeing a similar fate as the Banhs back in Saigon. And after retaking some high school courses to qualify for college, Sophie eventually completed her education and got a job working in a bank. This went well for several years, but it wasn’t exactly exciting or challenging for her, and she soon started having different ideas about what lie ahead.

Meanwhile, after first studying finance in college, then working for an insurance company as a junior accountant, and then finally pivoting to real estate for several years, Eric wasn’t loving the 9 to 5 life all that much either. After a while, he eventually decided to open another Vietnamese restaurant in Edmonton with a friend—much to the chagrin of the elder Banh—who just couldn’t figure out why any of his damn kids didn’t want to get real jobs! Mr. Banh just wanted the best for them, but he wasn’t seeing it in the restaurant business, and who can blame him? The restaurant business is a tough path to follow, and it typically ends in failure. That said, Eric’s Lemongrass Café did well, but he would soon be called south.

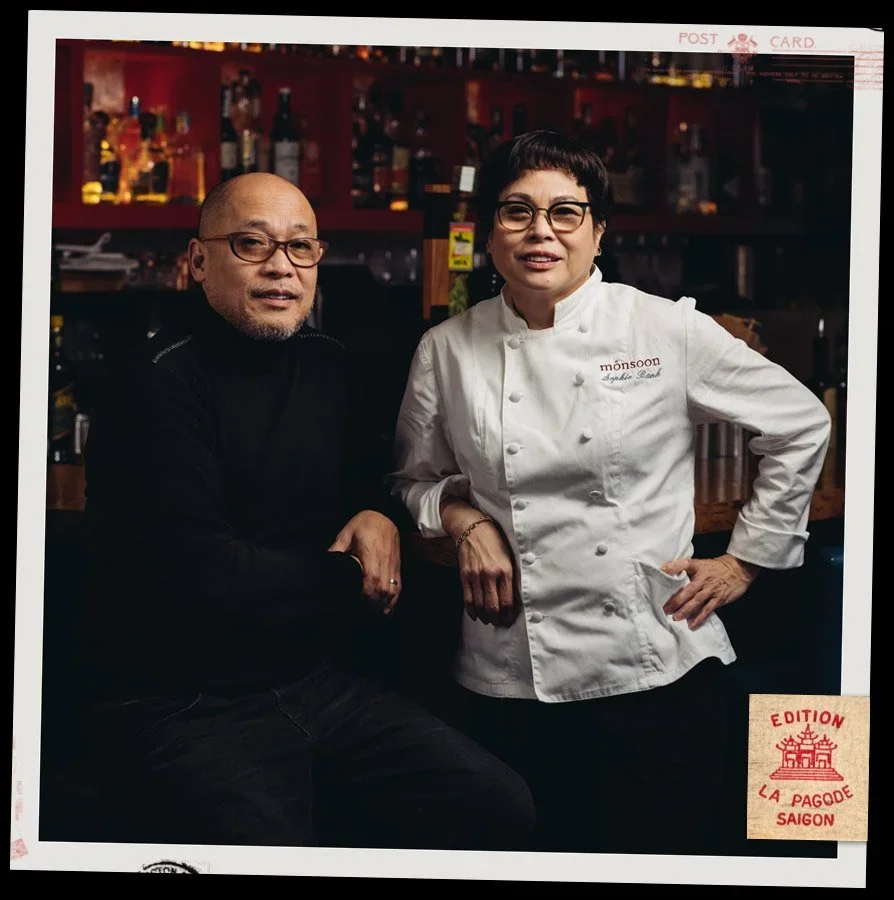

After a brief stint on the east coast, both Sophie and Sowady ended up in Seattle where Sowady took a position with the Washington Department of Transportation. Sophie enrolled the Seattle Culinary Academy at Seattle Central Comminity College where she excelled and eventually landed a job working for Obachine, Wolfgang Puck’s first foray into Seattle’s pan-Asian fine dining scene. She didn’t stay there for too long, as the real goal all along was to open a Vietnamese restaurant in Seattle. She eventually convinced Eric to come down from Edmonton so they could put together a restaurant concept that would become Monsoon.

Butterfly Wings

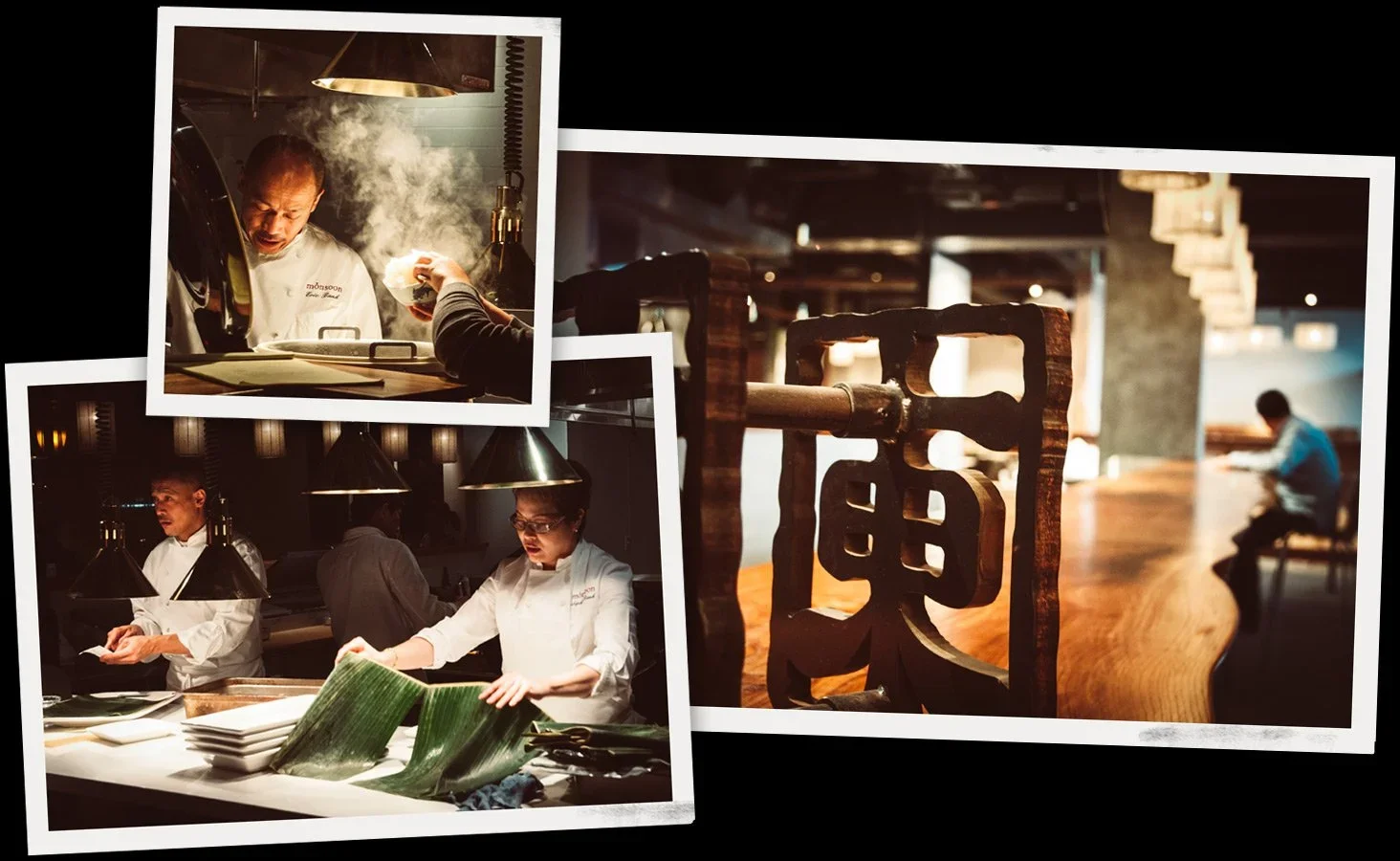

They knew they wanted to do something very different, as the typical formula for Vietnamese restaurants in Seattle was quite limited at the time. There were plenty of good phở joints, and a few places were doing decent sugarcane shrimp wraps and the like, but they really wanted to elevate the idea of Vietnamese cuisine altogether. They wanted to use local ingredients. Experiment with tradition. Push the boundaries of “ethnic” food. Introduce the city to something entirely new. Something original.

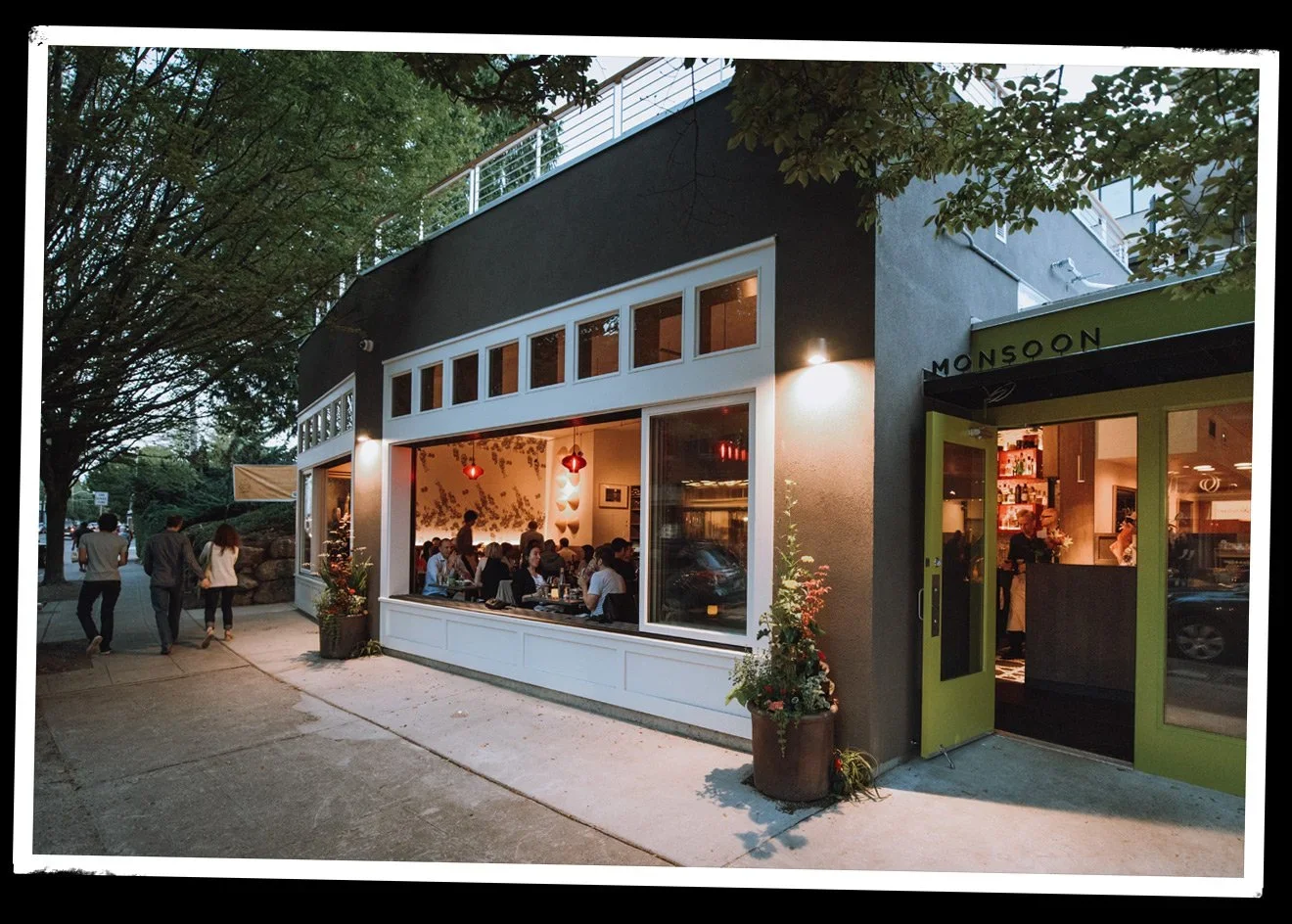

After much location searching, they were having a hard time finding a spot they could afford, so they went back to their dad’s old playbook. They approached a breakfast place on Capitol Hill, called Craig’s 19th Avenue Café, with a modest proposal. Craig’s was only open for traditional breakfast and lunch, so at night the cafe sat empty. Sophie and Eric proposed to transform the tiny cafe into a kind of “Vietnamese pop-up”. They would prepare and serve this newly-formed vision of Vietnamese cuisine during the night shift, right after the Craig’s crew had left for the day. And then, like cobbler’s elves, they would have everything cleaned up and prepped for the Craig’s breakfast crew before dawn. It sounded a little crazy, but everybody seemed to be on board. As they started preparing the menu for the first night of Craig’s Crazy Nighttime Vietnamese Pop-up Experiment, the phone rang. The owners of Craig’s had changed their minds. Instead of doing a pop-up, they wondered if the siblings wanted to buy the place outright. The price was right. Monsoon was born.

Taking Seattle By Storm

More siblings (and parents) were summoned from Edmonton to help remodel the former café into something a bit more interesting. The whole clan got to work tearing out ceilings and carving out a new space for the kitchen. Everybody pitched in. Sowady would work late nights after his day shift at the DOT. Mom and dad chipped in too—it was a real team effort. Yen planned to stick around after the remodel to run the front of the house, while Sophie and Eric would run the kitchen. About halfway into their demo work the City of Seattle showed up looking for permits. In the excitement of getting things rolling, they hadn’t bothered to get any, and the whole operation was shut down.

A couple of weeks and few fines later, they brought in architect Jeffrey Woodward to help concept a design and build out the space. The term “minimalism” was tossed around—partly for aesthetic reasons, and partly for budgetary concerns. The thinking was, if they kept things simple and pared down, they could hopefully save some money. Luckily, with a good architect, constraint will often breed creativity, and the final space came out perfect. It looks much the same today as it did on opening day. Woody (as he was known to friends) and Yen managed to hit it off during the whole process, and it appeared that a romance was brewing. She and Woody were married inside Monsoon several years later. They now have a daughter, Scarlett who is already in high school.

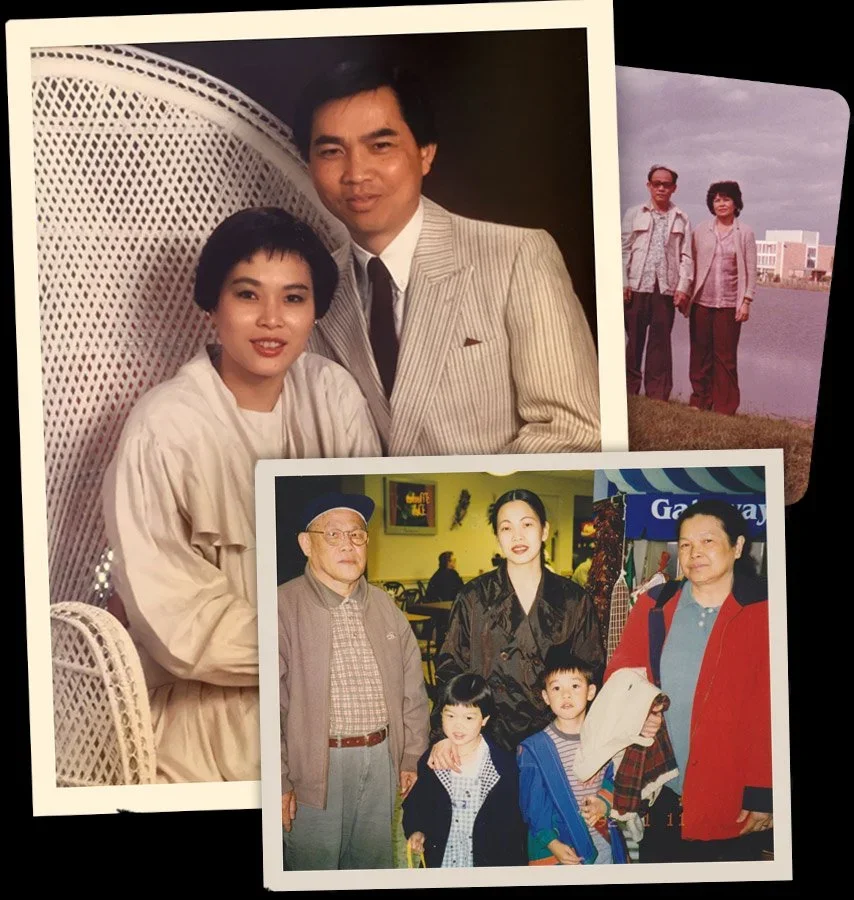

When they finally opened for business in early February of 1999, Monsoon became the first Seattle restaurant to reimagine Vietnamese cuisine. They also had to reimagine how a kitchen operates since they didn’t have enough money left for any new equipment. The kitchen line was made up of bus tubs filled with ice to keep things cold, they didn’t have a proper wok station, and the ancient stove left over from Craig’s had to be lit by hand each time and then coaxed to life with incantations. But somehow it all worked. They finally had a real restaurant and the future was looking bright. The Banh parents stuck around and helped out with the day-to-day operation. On any given day you could find mom furiously rolling spring rolls before the dinner shift, while Sophie and Sowady’s two young children did homework in the back. They brought in more staff and eventually middle sister Sydni would come from Toronto to help run the front of the house with Yen. They were all living under one roof again (this time Sophie & Sowady’s house in Shoreline) but things were a little less cramped than their earlier time spent on Bidong Island.

Since the dot com bubble was still being enthusiastically inflated, there was plenty of money in Seattle and people were hungry for something different to eat. Monsoon fit the bill perfectly: Seared Chilean Sea Bass, Tamarind Soup, Grilled Lá Lốt Beef, Red Bean Chicken with Taro Root, Wok Fried Red Chili Scallops with Dried Yam, Filet Mignon “Lúc Lắc” with Tomato and Butter Lettuce. This was the food the Banhs had been dreaming about for so long. Mom even had her own dish—aptly named Mom’s Tomato Tofu—and it was inspired by a dish she often cooked for the kids back in Edmonton. The Seared Chilean Sea Bass caught the tastebuds of one Seattle food critic who added it to a Top Ten Seattle Dishes of 1999 list. The Seattle Weekly called it “The best seafood they had tasted in this town.” The rave reviews kept pouring in. But sadly, what had quickly become the signature dish (Chilean Sea Bass), had to eventually be retired due to over-fishing and newly acquired “endangered species” status. This setback paved the way for the Catfish Claypot however, and it quickly took the mantle. The only real problem Monsoon faced was a line out the door every single night of the week, and that’s truly great problem to have. All that hard work finally paid off. Monsoon had arrived, and business was good.

Looking East and Beyond

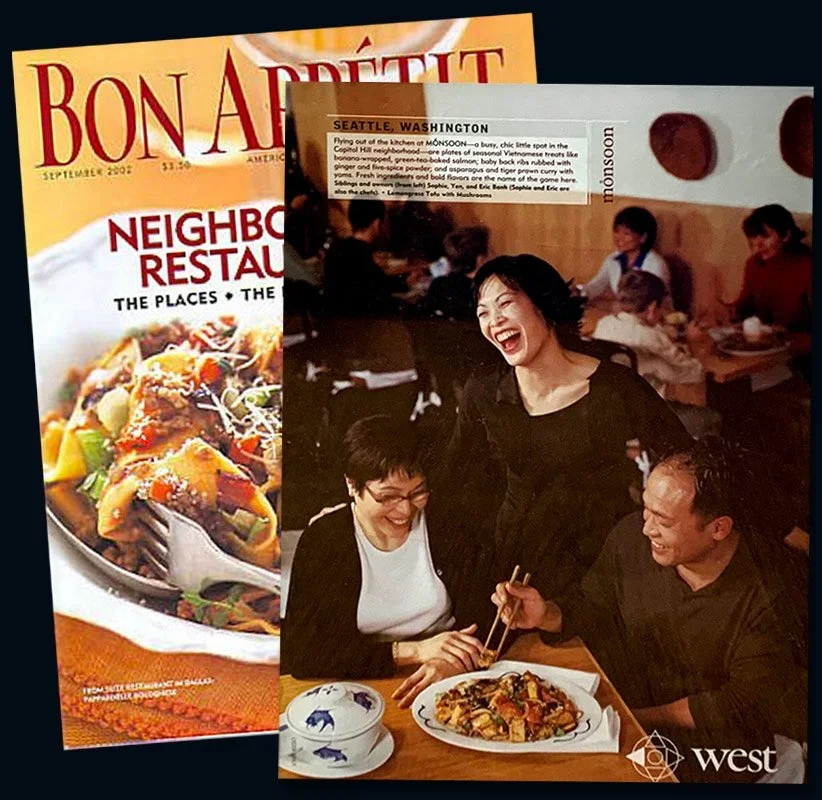

A few years later, after making many of the local “Best Restaurant” lists, Monsoon eventually got a full-page spread in Bon Appétit, and was named one of America’s Best Neighborhood Restaurants. Meanwhile, Eric had been curating a very deep and thoughtful wine list with inspired selections from Alsace and Germany. Wine Spectator magazine soon took notice and gave Monsoon its first Award of Excellence. To people in the know, Monsoon was not only the best place in town to explore elevated Vietnamese cuisine, it was becoming a great place to explore the world’s best wines.

Riding on their success, in 2004 the Banhs opened a sandwich place called Baguette Box off Melrose on Capitol Hill. This tiny shop served up creative bánh mì-inspired sandwiches like Crispy Drunken Chicken Baguette, Grilled Chorizo with Cilantro Rémoulade, and a daily selection of Salumi’s cured meats made to order. It was a fun, casual spot and a second location opened in Fremont shortly after.

By 2008 Sydni had long returned to life in Toronto and Yen was busy pursuing a law degree (“Finally!” says Mr. Banh), but Eric and Sophie were still going strong with Monsoon and Baguette Box. They decided to take the next big step and made plans to open a second Monsoon on the east side of Lake Washington in Old Bellevue. This time Albert was brought down from Edmonton to run the kitchen (he’s still there) and this second Monsoon opened to the public in December of 2008. Monsoon East, as it was called originally, had the same basic menu as the Seattle location with the addition of a seafood raw bar. Not to mention, a complete cocktail lounge that introduced craft cocktails to the Monsoon menu program and eventually inspired a bar addition to the Monsoon Seattle location in 2014.

Street Food & Cold Drink

Well into the market crash of 2008, the Banhs decided to create something a bit more casual and affordable with a strong focus on noodles and cocktails. They wanted a lively bar atmosphere with the potential for karaoke nights and Bruce Lee film screenings. Right around this time, Eric met his future (and current) wife Teresa Nguyen, and by the time they found space a year or so later, Teresa was on board as a partner in a brand new concept soon to be called Ba Bar. Teresa’s family had also made their way to the Pacific Northwest from Vietnam, and she had already been working at Boeing for 12 years when they met. Several years later, she would give up her career at Boeing to help run Ba Bar. She and Eric were married in 2019.

The Banhs ended up selling Baguette Box to some folks who had earlier made an offer on the restaurant. Baguette Box was doing fine, but it had a very limited ceiling, and the Banhs had slightly bigger aspirations. This freed up some much needed focus and energy toward this new concept.

Ba Bar opened in 2011 on Capitol Hill and quickly became a very popular spot to enjoy what the Banhs were now calling Street Food: Oxtail Phở, Bún Bò Huế, Mì Vịt Tiềm, Bún Chả Cá Lã Vọng—these street classics kicked off an innovative menu that also offered great bar food like Saigon Chicken Wings, Huế Dumplings, and Grilled Lemongrass Beef Skewers. Not everybody understood the concept of street food at first. One local critic who loved the food, didn’t think it should be called “street” food since a popular consensus in the west was that street food was synonymous with food trucks. This was an easy mistake to make, but as anybody who has been to Southeast Asia will tell you, street food is the best food. It’s food served literally on the street, with tiny tables and tiny chairs with huge crowds and lots of love. It’s not always portable, and that’s not the point. It’s fast food. But really good fast food. Occasionally it’s not even fast at all—but it’s so good! And even better when served alongside an inspired selection of expertly made craft cocktails. Ba Bar was a big hit.

If you are curious about the name Ba Bar, “Ba” means father in Vietnamese. Sadly, the Banh family patriarch, Mr. Banh himself, had passed away a few years earlier. The Banhs wanted very much to dedicate this next leg of the journey to him. His insistence on hard work and dedication to the family had truly paid off, and that same dedication and hard work lives on today.

Saigon Siblings and the Road Ahead

A second Ba Bar opened in Seattle’s burgeoning South Lake Union neighborhood in 2015 followed by a third at the very popular University Village in 2017. All locations are thriving, and the Street Food & Cold Drink formula has been distinctly popular. As mentioned, the Seattle location of Monsoon also expanded with a spacious cocktail lounge in 2014 and then a rooftop patio followed shortly after that, both Monsoons are still going strong.

Sowady had always worked part time at the restaurants, but in 2017 he retired from a long career in engineering at the DOT to work full time with the family. Someday he will retire for real. Sarah and Christopher (Sophie and Sowady’s kids) have long grown up and since graduated college. Chris is now following in mom’s footsteps and has spent considerable time learning the craft of cooking in both Cambodia and Vietnam. Keep an eye out for his pop-up one of these days. Eric’s son Laurence also came along in 2008, and you can often find him at Ba Bar waiting for dad to get off work.

Another restaurant concept presented itself in 2015, Seven Beef, which later transformed into Central Smoke. Despite good reviews and a compelling food and beverage program, neither concept could gain enough traction to sustain the endevour. Central Smoke closed its doors in January of 2020. Aside from recently kicking off a new Business Delivery & Catering program, the Banhs will stay focused on Monsoon and Ba Bar for now. You live and learn…

Sophie & Eric

A while back, as the restaurant empire was growing, the Banhs decided they needed to come up with a name for the collective group. Working with longtime graphic designer and photography collaborator Geoffrey Smith (who was also a waiter at the original Monsoon back in 1999!) they came up with the name Saigon Siblings. It was the perfect way to bring all the various concepts under one umbrella. The logo mark itself is also something you may have seen if you have spent any time in Southeast Asia eating street food: an entire family balanced on a single motorcycle speeding down the road to market. This was the perfect metaphor for these tenacious Saigon Siblings and their now extended families. Sticking together and moving forward as a team on the road to success. Always drawing on the inspiration of that struggle all those years ago, when they were forced to pack it all up and start over with nothing. Here’s to the road ahead…

—Saigon Siblings, 2020